South Dublin Heritage & Genealogy Centre History

A flavour of Dun Laoghaire Rathdown charts the expansion and development of Dunleary, as it was formerly known, from that of a blot on the map in the early eighteenth-century, its rapid rise to power in the 1800s, and its growing importance as a seaport to where the county stands today in the twenty-first century.

The eighteenth-century was a period of prosperity in Ireland, when the great aristocratic families of Ireland and Britain rivalled each other constructing testaments to the power and wealth of their families. In Dublin city an intensive building phase saw the establishment of many magnificent public buildings comparing favourably with that of London and other major European cities. By the close of the century, overcrowding in the capital and the continuing influx of wealthy merchants and speculators seeking property started the move outside the city of Dublin. We follow the move southwards to the small coastal village of Dunleary, being aware the proximity of Dublin had a large part to play in its development.

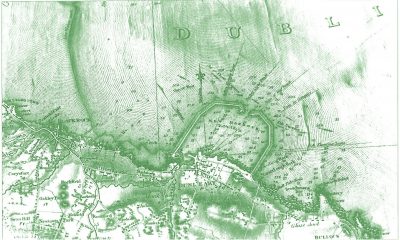

The Bay and Harbour of Dublin 1756

Dunleary 1700s

Dunleary appears on early maps as a small inlet along a rocky coastline about 11.2 km. from Dublin city. The name according to legend is derived from Laoghaire, king of Ireland, who established a Dun or Fort there in the fifth-century.

Dunleary was part of the lands of Monkstown, originally in the possession of Walter Cheevers, until the arrival of Oliver Cromwell in 1649. Cromwell, regarded as a military genius, came to Ireland with the backing of the English Parliament in order to put down the Catholics and Royalists, which he did with such ruthless efficiency that would rouse a lasting hatred throughout the country. Cheevers, a Catholic landowner, was among those whose lands were confiscated during the Reformation in 1653, and banished to Connaught, in the West of Ireland, to forage out an existence on barren stony land. Following the re-establishment of the British Monarchy in 1660, Cheevers regained his estate but it is not known if he ever returned there. Towards the close of the century the estate was sold to Archbishop Boyle of Armagh, and through the marriage of his two daughters, the lands became the joint property of Lord Longford and DeVesci.

The surrounding lands remained undeveloped until the middle of the century, apart from a sprinkling of fishermans’ cottages and a few isolated houses on the periphery. During this period a Bill was passed by Parliament for the construction of a harbour of refuge at Dunleary. The new harbour, when completed in 1757, provided shelter for large ships and fishing vessels when unfavourable weather conditions prevented entry into the Dublin Port (then the Liffey estuary).

The small cove quickly developed as a busy port of entry and departure for vessels sailing from Holyhead and Liverpool via Dunleary. The presence of large ships moored off the bay and the eventual arrival of passenger ships brought life and excitement to the emerging village.

During this period one of the most prominent buildings in Dunleary was the Coffee House – a large granite stone building standing high on an cliff, overhanging the creek. It was to become a welcome landmark for travellers following the long and sometimes hazardous sea journey. For those travellers journeying to and from Dublin in the 1700s, the roads were equally as hazardous, travelling by horse-drawn vehicles over roads that were little more than well-worn tracks. Arthur Young, visiting agriculturist, disembarked from the Clarmont sailing packet in 1776, following a twenty-two hour journey from Holyhead. Young, bound for Dublin from where he planned to commence a tour of Ireland, failed to record his impression of Dunleary on arrival, however, he later went on to express the magnificence of Dublin and the beauty of the South Dublin coastline.

In 1808 and 1809, the catastrophic lose of life through shipwreck in Dublin Bay prompted the urgent need for a larger and stronger harbour of refuge. Here, credit must go to Captain Richard Toutcher, a Norwegian seaman, who, horrified by the continual loss of life through shipwreck in the bay, wrote to the Port authorities, ‘I write not for fame but utility, but I have some nautical experience, and the idea of an larger and stronger asylum port at Dunleary, is ever first in my thoughts’. Toutcher, supported by Dublin merchants and shipowners, embarked on a long and forceful campaign, which eventually bore fruit when the first stone for the East pier was laid in 1817. The East pier was followed by the West pier. When the new Asylum harbour was complete in 1859, it was considered a monumental feat of engineering, enclosing 250 acres of water.

Kingstown 1821

The construction of the new asylum harbour a short distance to the East of Dunleary was the catalyst that saw the emergence of a new town as a frenzy of building commenced from the 1820s. By mid-century the small fishing village was unrecognisable behind a façade of Victorian elegance, with fashionable squares, bordered by fine terraced houses, two new yacht clubs, hotels, churches and public buildings.

Following a visit to Ireland by King George IV, and his subsequent departure from the new port in 1821, Dunleary was renamed Kingstown.

Kingstown 1800s

Socially the town was now enjoying the fruits of the new industrial age. The opening of the first railway line in Ireland – Westland Row to Kingstown – in 1834 contributed to the rapidly expanding economy, helped also by the existence of a busy harbour, where coal importing from Wales, and herring fishing was big business. The prestige and image of the town was further enhanced by royal visits and the presence of large pleasure vessels moored in the bay.

An added attraction to the now popular seaside resort was the Annual Regatta, or a stroll along the East pier to the sound of the regimental band. The Kingstown Regatta in 1898, was where Guglielmo Marconi, scientist, demonstrated his success with ‘wireless telegraphy’, by broadcasting the results of the Regatta, to the Daily Express in Dublin, while 15 km. from the seashore. Following Marconi’s experiment, Irish scientists used Kingstown Harbour as a base for pioneer experiments, that according to Dr. John De Courcy Ireland, maritime historian, ‘was of very great value for several important activities in most of the world’s seas and oceans’.

Behind the façade of grandeur and affluence, however, lay a deep chasm between the opulence of the wealthy, and the living conditions of the poor. The slums of Kingstown began with the expanding workforce, where no provision was made for housing the hundreds of new arrivals seeking employment, with the result, large families were housed in one or two-roomed hovels, without sanitation, light or fresh running water. The 1851 Census, records the population of Kingstown as numbering 10,500 inhabitants, for which the water-pump system became inadequate, hence, disease and cholera claimed many lives. Historically, during 1845-1849 Ireland was gripped by famine, emigration and disease of such catastrophic proportion that was to sow the seed for yet another great change in Irish history.

Dun Laoghaire 1900s

The new century saw Queen Victoria visit Ireland for the second time. Arriving on 4 April 1900, Victoria, disembarked from the royal yacht at Kingstown, onto a wooden pier , hastily constructed for her convenience. The reason for her visit, with only three weeks prior notice to the port authorities, was, ‘As a mark of gratitude to the Irish soldiers who were fighting bravely in the Boer War’.

Building continued in the town, at an alarming rate with the erection of a number of public buildings – Public baths, both fresh and sea-water, and wash-house facilities. The Pavillion, a large ornamental structure, which stood adjacent to the County Hall, Marine Road, provided leisure facilities, such as, tea-rooms, smoking and reading rooms, theatre and ballroom.

The early 1900s saw the end of British Rule in Ireland, and the newly elected parliament (Dáil) adopted the establishment of the Irish Republic, and the right of the people of Ireland to govern themselves. In 1924 Kingstown reverted to its former name, Irish spelling, Dun Laoghaire.

The War Years 1914-1918 & 1939-1945

The outbreak of WWI and WWII impacted on Dun Laoghaire, with the drain of young men and women enlisting for service, as soldiers, air and army officers and naval recruits, many of who would never return, their names are now recorded on memorials in local churches, schools, colleges and public parks.

Throughout the war years, the harbour gained in importance, becoming much more than a harbour of refuge, as first envisaged. The British Admiralty, who visited Kingstown frequently on manoeuvres, were quick to set up a minor naval base in the new port, The harbour continued operating a busy mail and passenger service, in addition to the frequent arrival and departure of military troops and war ships. The passenger and mail service ran relatively unscathed during the war, except for one of Ireland’s worst shipping disasters – On the 10th of Oct. 1918, the RMS Leinster, a mail and passenger steamer bound for Holyhead, was torpedoed by a German U-boat, UB-123, with the loss of 560 lives. A tragedy made even more poignant, just four weeks before the end of WW I.

The Aftermath of War

Unemployment and emigration followed the end of WW II in 1945, noted in Dun Laoghaire by the closure of the mountain quarries, as quarryowners, stonecutters and labourers, left Ireland, to seek employment in Britain and elsewhere. This changed the dynamics of the once close-knit community, as those that remained on the mountain turned to farming for sustenance. The mountain families would never fully recover the glory days and the buzz of active quarries.

In 1994 Dun Laoghaire became Dun Laoghaire Rathdown, and has since been governed by the County Council, which is now responsible for the planning and development of the region. The area today runs south-east of the capital, falling between the sea and the Dublin mountains, along the picturesque sweep of coastline from Blackrock to Bray. The entire region boasts ancient monuments, castles, mansions, villas and extensive parklands, such as Marlay, Cabinteely and Killiney, in addition to many green open spaces.

Dun Laoghaire Rathdown 21st Century

At the turn of the twenty-first century, Dun Laoghaire Rathdown continued to change dramatically with the construction of the M50 motorway, blasting ribbons of concrete inland throughout the county, changing the landscape for ever. Gone was the ‘most intact Victorian town in Ireland’, as described by the Hon. Desmomd Guinness, author of the Great Irish Houses. Although there still remains many fine examples of Victorian and Regency style architecture, complete with the original or restored cast-iron embellishments, they are somewhat diminished by the proximity of the modern steel and glass structures, that in the past, seemed to have appeared in prime locations overnight. Today, however, the value of older properties are now recognised by the county council, who have appointed conservation officers, to protect and restore historic buildings.

The Lexicon Library, one of the most recent state-of-the-art cultural spaces, adjacent to the harbour is regarded as a blot on the landscape to some, but demonstrating to many others all that is good in modern design, with the addition of research facilities and family friendly amenities.

Dun Laoghaire Rathdown with a population of over 2,000 inhabitants, embraces a multi-cultural community, evident by the variety of cultural events, housed both at the Lexicon Library and other local libraries, and also by the number of new restaurants, and smart coffee bars scattered throughout the region, catering for world-wide tastes.

The wealth of the county can still be seen in the number of yachts, and power boats, in the 240-berth Marina, opened in 2006, and also in the continuing demand for high priced properties, most especially, in the areas of Dalkey and Killiney.

The famed promenade, a beautiful tree-lined walkway, close to the east pier, is today likened by some to that of the French Riviera, especially during the spring and summer months, when the town and seafront is thronged with visitors.

![]()

The Lexicon Library

Conclusion and Summary

As we look back on old Dunleary, in the era of horse-drawn-transport and sailing ships, and the rapid change from a life based on ownership of land to a modern economy based on trade and manufacturing, to the 1800s when the resources of steampower had been fully exploited for fast railways and iron ships, for printing presses, photography, anaesthetics and the introduction of the telegraph etc., to the technological breakthrough of today in the field of science, space exploration and communication, we can only hold our breath in awe. What more can the twenty-first century add to the rich and diverse heritage of Dun Laoghaire Rathdown?